How Did I Go to War?

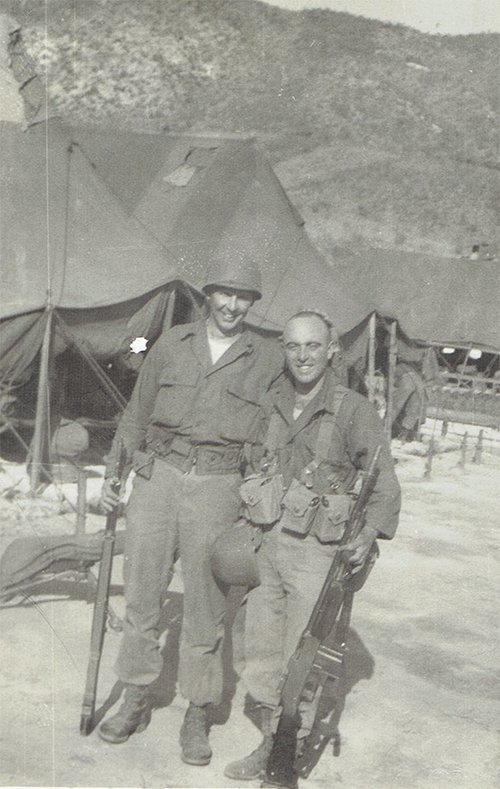

Privates Wright and Wolfe enjoying the landscape.

This is serious business. Is there a high school course that prepares a graduate on how to go to war? Of course not. So there I was a high school graduate, with an academic diploma standing near the top of an empty freight car speeding down a track while spinning its braking wheel to slow it down. I was moving toward a chain of empty freight cars destined for the Chicago stockyards.

Will this be my career, braking freight cars? I saw that my expiration date would soon be due as I sped down “The Hill”.

I left the 72ndSt. freight yard in Manhattan determined to quit this well-paying, but hazardous job. Upon my return home, a letter in my mailbox from the Selective Service System asked me to report for a physical. The Korean War had just begun and the UN army was at the Pusan Perimeter, near defeat. My body was needed. I was to report to 39 Whitehall St. in Manhattan for a physical.

“Okay. Bend over and spread your cheeks.”

The proctologist was checking for hemorrhoids. An amused and densely populated semi-circle formed around the doctor. He was addressing a peculiar character we knew from high school.

“Let’s try it again,.” said the frustrated doctor. “Stand here and watch how the next fellow does it.”

The next fellow dropped his shorts, bent over and spread his buttocks. With a mirror on his forehead and a tongue depressor in his hand, the doctor probed his sphincter. Satisfied, the doctor turned to this oddball and said,

“You saw that son. Let’s try it again.”

With his head making a U-turn and eyes fixed on the tongue depressor, he warily spread his cheeks. As soon as the depressor grazed his sphincter, he went into orbit, hurtling forward and scattering the men in a semi-circle.

The elderly doctor dropped the tongue depressor into a basket, shook his head, and then placed his hands on his knees. Frustrated, he told this peculiar character to move along, but to return in half an hour.

I was classified 1A and sent to Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania for basic training. Upon completion of training, our nasty sergeant, Nokel Roche greeted us.

“Congratulations,” he said. “You’re going to Korea!”

After 21 days on the Pacific, the M.S.T.S. (Military Sea Transportation Service) Simon Buckner brought us to Yokohama. We were given two pairs of new fatigues and an M1 rifle then we waited for a ship to bring us to Korea.

The M.S.T.S. Sadao Munemori was heading towards Inchon, Korea, with all the boys that had accompanied me on the Simon Buckner.

No sooner than I claimed a bunk, the PA system announced: “Breakfast is being served to Level One.”

A napkin? We never had one in basic training. I should have joined the navy. Breakfasts on the ship were haute cuisine compared to the cud and guts we received in basic training.

A chilly dampness crept under my fatigues and lodged in my bones. Maybe if I climb up to my bunk and get under a blanket I’ll thaw out.

To the ship’s rocking rhythm, empty cigarette and candy wrappers were floating back and forth in a large puddle of water below me.

I crawled to the top bunk, crept under my blanket, then a blare of static unwrapped me.

“Now hear this! Now hear this!” boomed into the sleeping quarters. ”On the port side of the vessel, our gunners will direct their fire at a white sleeve being towed by a Piper Cub.”

Where is port? Convinced that port will be where the GIs were assembled, I climbed two flights of metal stairs to the deck.

A crowd of GIs was on the left side of the ship. Off in the distance, a small airplane was approaching. The gunnery crew, sitting in an open turret alongside the hull zeroed in their 50 cal. ack-ack guns. A staccato of blasts erupted from the guns as the sleeve came floating by. Black bursts from the shells appeared; appeared far from the sleeve. Eyes were measuring the distance between the sleeve and the bursts when Intriglia yelled,

“If these guys are getting off the ship with us, I’m going home!”

The Inchon Korean harbor has the second biggest tidal range in the world. Tides rise then lower twenty-nine feet during twenty-four hours. Upon approaching the harbor, the tide was too low for the Munemori to reach port. The ship dropped anchor, and then Higgins boats circled around us. Munemori’s crew unrolled cargo nets that ran down the side of the hull.

“As you climb down the nets to the boats,” the PA system announced, “don’t, I repeat don’t hold the horizontal ropes, grab only the vertical ropes.”

“Damn it, what is horizontal, and what the hell is vertical?” asked Walters, a Nobel Prize candidate from Alabama.

As they climbed down, GIs who ignored the warning held on to the horizontals. They were swinging away and back to the hull. Some had to be lassoed, and then led down into the waiting Higgins boats. Darkness arrived with us by the time we reached port.

Bucky was alongside of me, but where was my buddy Dave Sohmer? Foolishly, I called out into the night, “Dave! Dave!”

From somewhere in the darkness he replied, “Wolfe! Wolfe!” This was accompanied by a chorus GIs, calling, “Dave! Dave!” then “Wolfe! Wolfe!” That was a failure. Fortunately, Bucky was nearby.

Trucks came to deliver us to a repot-depot (a replacement depot) opposite the University of Seoul. Under the roofs of squad tents, empty cots were soon filled with GIs who were with us on the Munemori.

In the morning, we lined up for breakfast accompanied by a large group of slovenly dressed GIs who did their time and were on their way home. Envy consumed me when I looked at their faded, shabby, worn fatigues, and then glanced at my dark, crisp, new, uniform. New indicated I was an untried rookie on my way to a hostile battlefield. Shabby indicated they experienced the trauma of war and were going home. But was it a hostile battlefield? The only suggestion was an occasional “boom” from cannons off in the distance.

A Korean civilian worker was rinsing our dirty breakfast trays when we heard a blast about fifty yards behind us. Accompanied by a siren, an army ambulance rushed over, but it was too late. A father was carrying his lifeless daughter who stepped on a land mine.

Three days at the repot-depot ended when trucks came to bring us to a railroad station. Unlike the Lionels in Japan, we boarded U.S.-size passenger trains

As we headed north, tall mountains crept upwards joining the rolling hills. In the distance, booming volleys erupted from 155mm canons. The train came to a halt in what appeared to be the middle of nowhere, A number of names were called out; among them was Bucky’s.

“Where are you going, Bucky?”

“They need medics.”

“You’re not a medic.”

“Living near the Bronx Hospital,” I told them in Yokohama, “I absorbed a good deal of medical knowledge so they assigned me to an EVAC (evacuation hospital).”

Only Bucky would have the guts to say that.

Bucky left, the train rattled on for a half an hour, and then came to a halt. “How do I go to War?” I asked myself.

“Grab your duffel bag and put on your poncho before you get off the train!” came thundering through the cars.

Where there might have been grass was a wide swath of mud welcoming our boots to the 15th Regiment, 3rd Division headquarters. A rotund colonel squeezed into a poncho, like the contents of an Italian sausage came out of a tent to greet us. With rainwater cascading off his shiny helmet, he barked,

”Leave your duffels here, put anything you will need in your backpack. The duffels will be waiting for you on your to return stateside. Welcome to the Third Battalion, the MILK battalion of the cream regiment (it consisted of companies, M, I, L, and K), the Can-Do Regiment, the Fifteenth Regiment. In our regiment we don’t day, “Yes, Sir”, we say, “Can Do, Sir” and, if you’re especially on the ball, you will say, “Have done, Sir!”

Am I back in junior high school? Am I really hearing this? Is he serious?

With my poncho shielding me from the rain, my sleeping bag in my backpack, and an entrenching toll hooked on to it, a GI led seven of us sloshing towards the MLR (frontline).

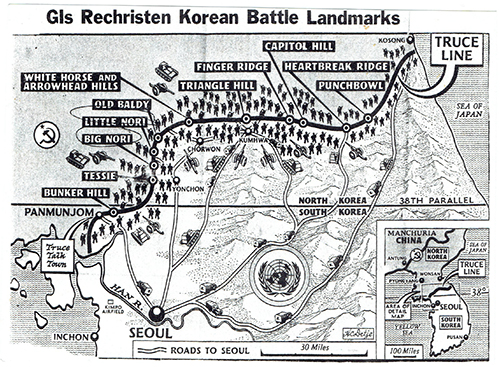

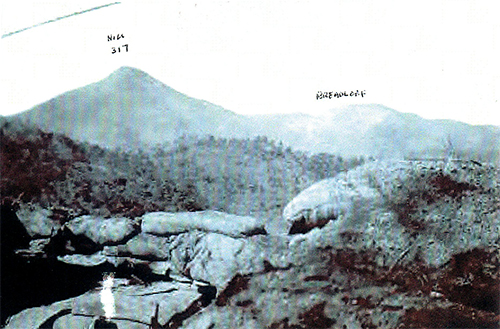

We arrived at Company L. The wide Chorwon Valley was spread out in front of us, framed by rising mountains. Sgt. Springer, our platoon sergeant came to give us an orientation. He pointed to the landscape on the far horizon and said,

“The tallest one is Hill 317. The adjacent hill, flat at the top, is Breadloaf, and the smaller, cone-shaped one is Sugarloaf. The nearby hill in front of us, right there, is Mary OP. In a few days you’ll be paying Mary a visit.”

While scanning the landscape, my impression of Korea was hills and mountains of brown dirt, occasional clumps of grass and some mangled trees.

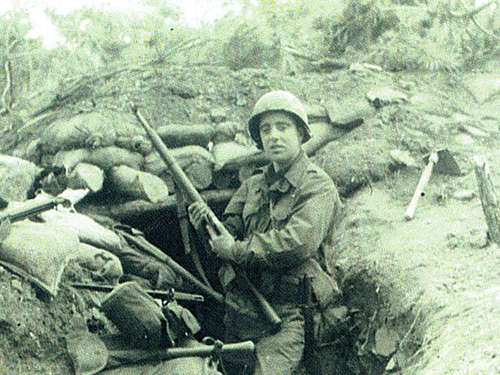

The platoon was scattered in 6’ x 8’ bunkers along a trenchline running east to west. Sgt. Springer handed me a B.A.R. (Browning Automatic Rifle), two full magazines, and then he led me to a bunker. He introduced me to my roommate, Jesse.

Am I going to live here? Can I live here? I looked down at the damp, dark, hole-in-the-ground and asked,

“Where do we sleep, Jesse?”

“Lay down your poncho and put your sleeping bag on top of it,” he replied.

“What? My mattress at home had springs popping out. My mother laid a blanket over it, but this?”

“You’re not stateside, you’re not in the tanks or the artillery. Welcome to the infantry.”

Then he recited these lines from a blues song by Brownie McGhee:

Rocks have been my pillow

The cold ground’s been my bed

The stars have been my blanket

And the blue sky’s been my spread.

In twenty minutes, Sergeant Springer came to tell us a patrol was going out tonight. He assigned Russell Wirt and me to guard the Free Lane, an unmined path leading from our position and into the Chorwon Valley.

In spite of the barbed wire, bunkers and occasional artillery bursts, I still didn’t feel as if I was in a war zone.

Nighttime arrived, Russell was terrified. His brother was killed in WWII. Throughout the night, his teeth screeched against each another while he was sleeping. After an hour, I heard an exchange of fire. Within fifteen minutes, the patrol returned with their wounded. A medic asked me to hold down a wounded GI squirming like a cut worm, while he administered morphine and then plasma. The GI was carried to a litter Jeep then taken away. It was a chaotic night. This was my answer to, “How Do I Go to War?”

The following morning, the sun replaced the rain. I crawled out of my bunker and looked down at a brown field of clay; my front lawn. Scattered on the slope were lonely patches of green framed by empty C-ration cans. Like large, coiled Slinkies, concertina wire, lay scattered over the entire area.

“Don’t ever walk on the slope in front of us, warned Jesse. It’s mined. Over there, to the left is a barbed wire fence, that’s the Free Lane. We walk there safely when we leave and return from a patrol.”

Sgt. Springer came to tell us that coffee was ready on the reverse slope.

“After breakfast, go with Wright and bring back a couple of barrels of water from the pond.”

The trip was like traveling through the remains of once lush forest. Bare trees and tree stumps were littered around us. Scraps of grass made a meager attempt to recover and return to the original greenery.

Four days later, our platoon was assigned to patrol a mile into the Chorwon Valley. Recalling the night when I guarded the Free Lane my head became entangled in a web of “What ifs”.

What if we meet the Chinese will I freeze? What if my buddy was hit, do I leave him for the medic, or do I tend to him? What if I got hit, will the medic see me, or will I be abandoned in the valley? What if I am taken prisoner? What if I return up the Free Lane, will I remember the password? What if my parents get a telegram, “I regret to inform you…”

So, this is how I went to war..

Edited from Cold Ground’s Been My Bed: A Korean War Memoir by Daniel Wolfe

danielwolfebooks.com